Note from the Editor of H|M|S

This year’s Baselworld wasn’t just one more edition in a series, but it wasn’t exactly the quality of the watches on display that made it special. The fair took place against a backdrop of two significant threats. If it were a film a suitable name might have been “Dark Clouds in Swiss Watchmaking.” Those dark clouds are, on the one hand, global economic factors which, taken together, sound alarm bells and paint a generally bleak picture. And on the other, the appearance on the scene of smartwatches, particularly those by Apple, announced just days before the start of Baselworld.

In the interviews with H|M|S, brand executives were willing to speak of their current hopes and fears. And their opinions, quietly expressed in confidence by people in the industry, on stands, in corridors and cafés, added up to a situation of concern.

Don’t get Smart.

The arrival of smartwatches that can be connected to the telephone has raised the alarm for the Swiss watchmaking industry. Mere memories of the damage that the appearance of quartz and Japanese watches inflicted in the ’70s still produce shudders.

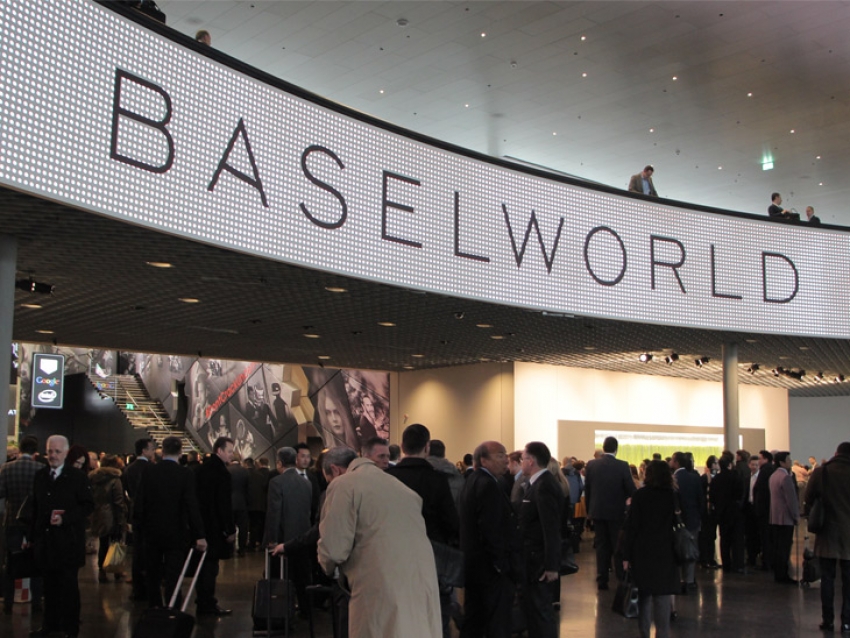

How did the world of Swiss watchmaking react at Baselworld? The initial impact was a shock in itself. By simply standing at the entrance, even before passing through the turnstiles, the sight of the Tag Heuer logo placed next to that of Google, and especially that of Intel, was an unavoidable talking point at the fair (see photo in the gallery of this article).

Tag Heuer announced that it is to create a watch jointly with those two companies. In other words, it is linking its name and the expertise acquired in the Swiss watch industry, plus the skilled craftmanship of micromechanics (let’s not forget that in 2012 it won the “Aiguille d'Or” [Golden Hand], the top industry award at the Geneva Watchmaking Grand Prix for its Mikrogirder watch), to nothing less than the largest manufacturer of chips in the world, which is Intel.

The off-the-record comments we collected were varied, but none was precisely indifferent. “They’re shooting themselves in the foot,” said the marketing manager of an important brand. “It’s a masterstroke by Jean-Claude Biver,” said someone in a much more positive vein, even though they don’t work for the LVMH group.

We passed on this concern to Guy Sémon, General Director of Tag Heuer, during the interview he granted us for the cameras of H|M|S.

_ Could this agreement with Google and Intel lead to a loss of Tag Heuer’s identity?

_ “No. This is like with the car industry. If you compare cars from the ’70s or ’80s with those of today, you’ll find that nowadays cars contain a variety of electronic devices, such as the GPS. But if you buy a Ferrari, you do so for emotional reasons. We aren’t yet sure what will happen in the connected watches segment. But if I want to know where a train is going, what I have to do is buy a ticket and get on. And that’s what we’re doing.”

The quietly mentioned arguments we heard to dismiss the threat posed by the coming technological wave were, for example, “Who’s going to buy a watch with a battery that only lasts 18 hours?”, or “Who’d want a watch that’ll be old in two years because a new model has come out?”

However, when the time comes to switch on the microphones, we also hear some very interesting answers and analyses.

“Seventy per cent of Americans, for example, do not wear a wrist watch. So smartwatches are an opportunity for many people to get used to wearing one, and of course to then opt for emotional and mechanical time pieces, like those from Switzerland,” Patrik Hoffmann, CEO of Ulysse Nardin, told us.

In the same line of thought, Ricardo Guadalupe, CEO of Hublot, gave us his insight: “Switzerland produces 20 million watches a year, but there are many people around the world who don’t wear a watch. Although I think the segment of watches costing between 300 and 600 dollars may be affected by smartwatches, it represents an opportunity for others.”

So, Guadalupe and Hoffmann view the arrival of smartwatches in a favourable light, as a form of growing the market for watches. But neither Hublot nor Ulysse Nardin has yet produced connected watches, in contrast to Tag Heuer.

Alex Magada, who was attending his first fair as CEO of Zenith, gave us a different perspective on what the real threat might be, and how it should be addressed: “What is it that is making some manufactures feel threatened? Smart watches? Or the fact that Apple could be recognised as a luxury brand? Whatever it is, I don’t think it matters. The important thing is that we should be innovative and intelligent enough to offer the public new products and new interests,” he said.

Other brands, such as Bulgari, Frederique Constant and Breitling, also presented connected watches at the fair.

By contrast, Omega chose to emphasise the traditional technology employed by Swiss industry by presenting a chronometer that beats the famous COSC parameters. And when we consulted their president, Stephen Urquhart, on his vision as to what impact the appearance of smartwatches will have on Swiss industry, he was categorical: “I have learnt in life to be very careful about making predictions. It’s time to wait. Do you know what? Come back next year and we can have the same conversation, but we’ll know much more by then …”

Global economy, with little power reserve. The cocktail affecting the finances of the watchmaking industry contains ingredients from all around the world: revaluation of the Swiss franc; devaluations in Russia, Mexico and Brazil; anticorruption laws in China.

“If we wanted, our brand could take two years of its worldwide production and sell it all in just one year in China,” an important executive told us, strictly off the record, two years ago. Nevertheless, since then, the Asian giant has implemented a fierce anticorruption crackdown that has had a strong impact on the sale of gold watches and has actually led to a fall in world demand for the precious metal.

“Swiss watch exports fell 5% in February.” With that laconic phrase the CEO of a leading brand defined the situation at Baselworld, while we were putting on his microphone for the filmed interview.

We naturally wanted to check that information, and in the February report on the official site of the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry we found that compared with February 2014 the drop in exports of watches of over 200 Swiss francs was 4%, in gold watches it was 6.1%, and that exports to Hong Kong declined by 21.8 per cent. Expectations now lie in the growth of the United States and Europe (the complete report can be seen at http://www.fhs.ch/scripts/getstat.php?file=comm_150202_a.pdf)

Speaking in the corridors of Baselworld with executives and retailers working in our region, Latin America, the topics of conversation weren’t the new tourbillion of a brand from one place, or the repetition of minutes of a brand from somewhere else. The topic was foreign currencies. “Switzerland has revalued the franc. The last time I looked, in Mexico the dollar was around 16 pesos. Brazil’s devalued, Argentina is still a problem, and Venezuela… well, what can we say?” were the words that best reflected the situation.

If you can’t beat them…

Of the two threats, the most worrying is, without a doubt, on the economic front. But unfortunately the variables in play are beyond the control of the watchmakers.

By contrast, the arrival of smartwatches, which have placed watchmaking on the front page of the world’s newspapers, poses a new challenge. But if extreme conservatism is hardly a good prescription, “joining the enemy” could indeed be very dangerous.